How Do I ~ Climb A Mountain?

Where do we start with climbing? At the bottom, obviously.

Where do we start with climbing? At the bottom, obviously.

Keep reading, there's more golden nuggets where that came from...

Climbing is something that fills all of us, no matter what our skill or experience, with varying levels of anticipation, excitement and dread.

Even the worlds greatest climbers

are always

afraid that someone, something or even the climb itself,

will beat them.

But it doesn't have to be that way for us mere mortals.

Everything is doable. You just need a capable, coping strategy to help tackle the perceived big problem.

This factsheet is for mountains and big hills. The principles are the same, just the pain lasts longer on one than it does on the other!

Climbing, or the thought of climbing, gives more people, more problems than almost the rest of the other cycling disciplines put together. But it needn't be that way. We're not afraid of what we think we are afraid of; we are afraid of what we think!

Here's how you break down those seemingly insurmountable problems in to manageable chunks. Here is how you can tackle your worst nightmare; this factsheet won't make you a grimpeur but it will help you grimp.

Master The Technique

Climbing is an art;

an art you can master. There

are many things you can do to make yourself a better climber, and the

main one is to "climb like a climber". Which sounds a stupid statement

but let's talk it through.

Some people climb like they're wrestling an octopus. Arms, legs, shoulders, head, bike, everywhere.

Cycling is, and always will be, about economy of effort and never is that more true than when you're going uphill.

First

off, sit like a climber. Sit

a little further back on the saddle than you normally would.

First

off, sit like a climber. Sit

a little further back on the saddle than you normally would.

This is where the fantastic "extended" fizik Arione saddle is a God send. I bought my first one in 2004, about a week after they launched; how everyone laughed.

Within a month I'd bought five, one for each of my bikes, even my turbo bike! They're that good. People stopped laughing at them a long time ago. Fashion? A fickle mistress.

Perch yourself off the back of your saddle of choice and push down like you were pushing your feet in to a pair of wellies (gum boots for our foreign friends). Keep your back as straight-ish as you can, with your hands on the tops.

When you pedal, make a conscious effort to drop the heel slightly at the bottom of the stroke and pedal in full, fluid, circles. Feel the power just forcing through the pedals.

You can sit more upright on a climb because you're not normally at an aerodynamic disadvantage. Your main priority is to get an uninterrupted flow of air in to your lungs, and from there, in to your muscles. Hands on the tops, a straight back and open chest will facilitate this.

Keep the arms relaxed (although when the going gets tough you can pull on the bars) and try everything you can to relax the upper body and keep the shoulders steady. It's easy to see when someone's in trouble on a climb; watch for the drooped shoulders. If you're in a race and the rider in front starts to drop their shoulders, give it a dig if you want to lose them.

So there it is; rule number one! Keep still, keep relaxed, keep pedalling. Make a conscious effort to do this and if you're out with mates, keep an eye on one another and keep reminding them, and make sure they remind you. You will be amazed at the difference concentration makes to your forward, upward progress.

Standing or Sitting?

Standing or Sitting?

The big decision. Each has its merits

and there's a time and place for both.

Generally, the gradient will determine your position on the bike. But climbing a 20 kilometre mountain seated will hurt your back and hurt it bad.

Trying to climb it out of the saddle would just be just as wrong on so many levels!

There will be times when you need to get out of the saddle just to stretch your back and just to shake the neck, shoulders and arm muscles loose.

Sitting hunched over the bars tightens the muscles and muscles don't like being tight.

So mix it up on big climbs and gradient changes if you want to make the best of a tough situation.

Climbing seated is around 8-12% more efficient than standing.

But there comes a time when standing is a must; so how do you know?

The Numbers

Obviously we're all different but the general

consensus (peer reviewed, anecdotal, my power meter) is that seated

is best and here's why.

Standing causes you to use more muscle mass (arms, shoulders, core), which "obviously" demands more oxygen provision to service that muscle mass requirement.

Standing gives a lower perceived effort which (again obviously) is what we're all trying to achieve; isn't it? But at the cost of increased oxygen consumption and heart rate? The results of which cause long-term issues, and not in a nice way.

Higher oxygen demands require a higher heart rate to help meet that demand. The higher power output will also cause higher lactate build up. So when you stand, stand sparingly and get it over and done with quickly. Before you cause more problems than you solve.

When standing, the tip of the saddle should just brush your (inner!) thighs. Don't hang over the front of the bike. I've only ever had to do this three times in my life; the Koppenberg, La Redoute and the stupidly steep Muro di Sormano. So no heroics.

Over the bars, isn't a good look and it doesn't make you any quicker. But it does stop you toppling backwards. Unless you're on one of these three, keep your weight central over the frame and between the bars and saddle. Remember, breathing cleanly is your priority.

Pedalling Rhythm

The

preference to sit needs to be balanced against the need to

maintain efficient forward momentum. When the gradient

increases, and the revs drop, you need to use more muscles, and

more power, to keep your cadence in the happy zone.

Tim O'Sullivan climbing the 30% section of Fred Whitton's

Hardknott Pass

Photo: Steve

Fleming

This happens generally on the inside of hairpin bends and switchbacks, or when a particularly vicious ramp kicks up in front of you.

This is brilliantly demonstrated in Steve Flemming's fantastic sequence shot of flamme rouger Tim O'Sullivan on the mighty 30% gradients of Hardknott Pass; rated the toughest climb in the UK.

While those around are walking, Tim Stays in the saddle, then just before, he hits "the steep" bit, he gets out of the saddle and launches the bike forward, in one, smooth, uninterupted movement.

At this point, and on gradients like this, it's imperative to a) keep the front wheel down (especially when turning a corner) and b) stop the back wheel from spinning (especially in the wet).

This couldn't be a more dangerous situation! But a brilliant use of technique, skill, strength, balance and fluidity, means Tim can keep going where many hundreds of others couldn't.

If you're in a race situation, there may be a need to attack the inside corner out of the saddle to gain an advantage over those taking the long way round.

Use this technique to get out of the saddle, get through the corner, and get sat back down, in the right gear, at a cadence that best suits you, as seamlessly and quickly as possible.

The optimum cadence is different for all of us but the technique isn't. At all times your objective should be to pedal fluid, neat, steady, circles.

Stomping on the pedals isn't conducive to a good experience. Keep your foot steady and level and just drop the heel as you push down to the bottom of the stroke. No pointy toes.

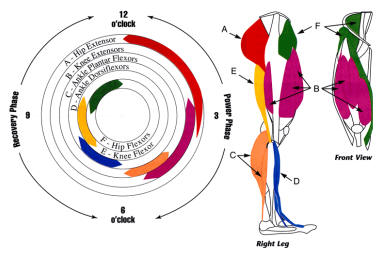

I'm not in to all this, "pull up with your opposite leg

business" and "scrape mud off your shoe" but I do like to

concentrate on smoothing out the pedal stroke to keep a

circular pattern with a steady power application for a full 360

degrees.

I'm not in to all this, "pull up with your opposite leg

business" and "scrape mud off your shoe" but I do like to

concentrate on smoothing out the pedal stroke to keep a

circular pattern with a steady power application for a full 360

degrees.

Always try to stay on top of the gear and find the sweet-spot for your pedalling comfort. Don't try to hold 100 rpm, just because your mates do. Do what suits you, just do it quickly and efficiently!

Breathing...

Is important. Yet another pearl of Williams wisdom! It's so

easy to fall in to the trap of letting your breathing get

ragged and out of tune with your body. Concentrate on your breathing as much as

you do on your pedalling. In fact the two are very closely linked.

Breathing should be deep and rhythmical, not shallow and snatched. Once you start ragged breathing, ragged cycling quickly follows.

It's a cause and affect situation. You take a shallow breath, you can't feed your oxygen requirements, you start to go in to oxygen debt, you panic, you take a snatched second breath and the decline in to oblivion has already started.

Pay very, very, very, close attention to your breathing patterns and synchronise them with your pedalling efforts. When you get the two in to some sort of balance it all begins to flow. You won't necessarily be quick but at least it's sustainable until you regroup your resources and feel confident to kick on again.

Fausto Coppi Sportive ~ Cuneo

Riding the Top of the World!

Breathing control is absolutely vital when you're climbing in the mountains. Most of us sea-level dwellers completely forget about the strangulation effects of altitude. It's the invisible hand around your throat that steals oxygen from your lungs.

Oxygen content in the air we breath is around 21%. It's still 21% at altitude but the air pressure at the top of a mountain is lower than that at the bottom, so the effect is that of the air being "thinner".

At 2115 metres, which is the top of the Tourmalet, there is 78% of the atmospheric pressure found at sea level. So we only get 78% of the expected oxygen molecules in to our body. Which makes a bad situation 22% worse! If you don't think this is enough to affect you, how would you feel if you were given a 22% pay cut?

Now you have this information, you can use it (and your power meter) to make sure you "power back" to a sustainable threshold as you climb any given mountain. I'll come to that later.

Attitude not Altitude

Fight or Flight? It's how you prepare mentally, not just

physically, for any climb that will determine your path to the

top.

Will it be a hard slog where you embrace the pain and take on the world? Or is it going to be a fight against nature where the whole world is against you and you're looking for excuses to bale out at the first opportunity?

Climbing is hard, of course it is. That's why we do it! If cycling was easy it'd be called football. Soccer for our American cousins. So let's not kid ourselves this is easy. Expect a hard time and suck it up. Bring it on, find your limit and ride just below it. The rewards for conquering your first mountain last you a lifetime.

Weight ~ Yours not the bike!

Your

speed/comfort/enjoyment when climbing is

primarily governed by your power to weight ratio. However, there

is a law of diminishing returns.

Your

speed/comfort/enjoyment when climbing is

primarily governed by your power to weight ratio. However, there

is a law of diminishing returns.

There's more on this subject in the Climb like a Pro factsheet, so I won't trouble you with all that information here.

However, for a 70-odd kilo rider, it's easier to lose two kilos than it is to gain 15 watts climbing threshold. Because they're the numbers you need to hit to maintain the same power to weight ratio.

Losing six kilos could put a six-foot, 70 kilo rider in to serious health issues. Apart from losing weight, you'd probably lose around 70 watts of power so you'd be in even bigger trouble if you tried to climb a mountain. You'd be lucky to be able to leave your sick bed!

So,

everything in moderation. I'm sure the vast majority of us could

probably lose a kilo or two when we take on the big mountain

challenges.

So,

everything in moderation. I'm sure the vast majority of us could

probably lose a kilo or two when we take on the big mountain

challenges.

Just don't go mad, keep an eye on your health and once you're back to sea level, let a kilo or so slip back on again. We're not pros and you don't want to look like Wiggins in the photo above or Rasmuusen in this shot.

It's not a good look and you ain't going to pull on the beach in the summer. Especially if you've got mahogany arms and a body that's Daz white!

Gears and Wheels

If you want to climb better, lighter wheels

will help. Carbon ones are nice but you really don't want to be

descending super-fast descents you don't know, especially in the rain,

on wheels with, what can best be described as, an inconsistent braking

surface.

Go light, go alloy and lay off the cream cakes until the day after your big climb. Wheels will help you far more than a lighter frame, saddle or handlebars.

When I started these sportive jobbies in 2003, I had a standard chainset but went large at the back. For 2004 I looked at the events I was doing and threw on a triple chainset, it's all that was easily available at the time. I hated it!

I found myself selecting the inner chainring through fear rather than necessity. I remember climbing the 29 kilometre Col de Portalet in the Quebrantahuesos in the inner ring and suffering the whole way up. I was just going so slow!

In 2005 a compact (that were slowly becoming available) was fitted and I've never looked back. You get the best of both worlds and can easily find a gear for the steepest, longest, baddest of climbs and still have a big enough gear for the sprint on the flats.

Having said that, I climbed Alpe D'HJuez in 58 minutes (to the proper finish!) on a standard chainset. So be brave if you feel you can be but a compact is really the way to go for full enjoyment.

Power On

Now we come to my favourite subject. Trust me, nothing will get

you up a mountain quicker than climbing just below your "blow

your nuts off threshold".

One of the biggest problems you'll have climbing mountains or hills in foreign sportives, or any new event, is knowing where the top of the climb is and what the gradient is actually going to be doing around that corner.

When climbing I try to hold a pace I know won't cause me to blow. In the mountains this is around 220 to 240 watts. Now I know this doesn't sound a lot but it is sustainable. I held this strategy for the Ventoux Master Series Challenge, well I did for the later rides, and banged out some remarkably consistent and repeatable efforts.

As I said, this figure isn't high, but it is possible (for me) to hold it for two hours or more in the mountains and their rarefied air. As I mentioned above, you have to allow for the gradually decreasing oxygen availability at altitude.

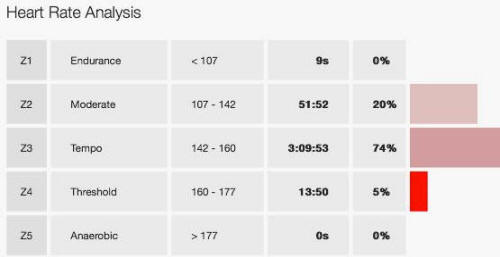

You can see from this diagram, that local rider, Chris Burrough used this strategy to perfection in riding to 9th place in the 2014 Morzine Haute Chablis sportive. Although riding to power on the climbs, his heart rate trace shows how he kept at exactly the right level for four hours!

An absolute textbook case of how to ride a mountainous race

Your objective is to find what works for you (be it power or heart rate) and stick to it for the duration of the climb. One of the great climbing pleasures is to see those that left you behind at the bottom of a climb, coming back to you, being caught, getting passed and then dropped like a stone, a kilometre from the summit.

A

microcosm of this in action is when we ride our Classics

Circuit here in Jersey.

A

microcosm of this in action is when we ride our Classics

Circuit here in Jersey.

One of our speed-power climbs is 90 seconds long and is climbed at an average of 400 watts.

In the early winter weeks we hit it at full (winter) speed and try to hang on as long as we can.

If nothing else it keeps us warm.

We end up with a (yellow) power profile like the one above, not pretty. A big 500w spike at the start that peters out to around 200 watts as we crest the top, in a basket and fit for nothing.

Here's

the same climb come March and April. Much more measured, a steady

(green) cadence and fairly consistent (blue) speed profile.

Here's

the same climb come March and April. Much more measured, a steady

(green) cadence and fairly consistent (blue) speed profile.

The peak power is lower but the minimum power is much higher and the average is higher by around 20 watts.

The big difference now, is that when we get to the top we attack. We've climbed it quicker, with less physiological stress and with more reserves available come the summit.

In May, this training paid off when I took ninth place in the Ble D'or Sportive, attacking on the final climb and sprinting to the finish.

don't look back

Hydration & Nutrition

It's always difficult to eat and

drink on a mountain (you shouldn't need to on a hill!) but you

need to fuel the engine and the brain. So here's the best way.

Around 10k from the base, fire a gel down your throat and take a swig of drink. This will kick in on the early slopes.

When you're a kilometre or two form the base take a couple of bites of a power bar and get it down your throat and settled before you start your ascent. As you reach the base, take a sip of drink again. This will kick in higher up the climb.

Don't eat too much as you'll divert blood and fluids to your stomach and could get a bloated feel. It's tough enough climbing without having added gastric distractions!

When you get to a sweeping bend, go wide, find a flat bit and learn to get your bottle out of its cage, in to your mouth and back in the cage in four pedal revs. Do this often.

There should be no need to take a second gel on the mountain but there will always be a need to drink. Save the gel for the descent especially a caffeinated one. It'll help you concentrate when cornering at speed and keep you alert when slightly fatigued.

The flamme

rouge Pyrenean raid; QOM's and top tens

galore June 2014

Mark Shaw, Susan Williams,

Kat Guillemot, Steve

de Sousa, Lou Shaw & Steve Guillemot

The Message

How do you climb a mountain; a kilometre at a time.

Climbing mountains and big hills are what stand us out from the commuting crowd. Don't be afraid of them (mountains, not commuters). Ride them like you would ride in to a headwind. Stay steady, don't fight the bike and keep within your limits, don't try to match the limits of those headstrong fools around you.

Food is important, drink is essential. You'll be doing a lot of breathing on a mountain and if you've ever climbed one in the cold you'll see the steam pouring from your mouth like fire from a dragon. Well that's not fire, it's water. So remember to drink.

Stay seated but stand when you have to. Find a rhythm that suits you and keep your weight in check if you want to enjoy it more. Because it can be one of the most enjoyable days on a bike. Conquering mountains and nailing descents. (Went up Alpe D'Huez in 58 minutes, came down in 11:08) It really doesn't get any better.

But finally, do what's right for you. Take the bits of this article that work for you and ignore the rest.

Now go and find some big hills, take them on and book yourself on a sportive that takes on the classic climbs.

Suffering has its rewards. Suffer well my friends, suffer well.