Cadence & Winners

Cadence is one of those things that often gets overlooked in the spectrum of training variables. Everyone talks watts, heart rate, hours, distance, hills climbed, stress scores, and, for those living in the smoke and mirrors world of power meters, ATL's, CTL's, IF's etc, etc, etc.

You rarely hear anyone mention their cadence. Well cadence is important and I'll try to explain why, right here...

What is it?

First a definition; cadence refers to the average number of

revolutions of the pedals per minute. It's how fast you're

pedalling and it's measured in rpm, revs per minute. So simple

it's ridiculous.

The problem now comes in describing at what cadence it is best to pedal. Whatever you answer, you're wrong. It should be faster. At the end of the day (or the race anyway) the person that can spin the fastest will probably walk away with the spoils. But that doesn't mean you should ride the whole event at 140 rpm. And here's why.

Gears & Cranks

In the good old days, when sex was safe and car racing was

dangerous, we used to ride six speed, straight through blocks and a 52

outer chain ring with a 42 inner.

Here's one of my old Shimano 600

blocks that I keep as a paper weight. It weighs 330 gms!

The gearing is 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 teeth. And we used to do

Round the Bays on bikes that weighed 23 lb's!

Think of that when you're next riding up Bonne Nuit with your 50x34 and 27 rear plate.

Sorry to our international readers for getting all "local".

Gearing choice was much more simpler in the 80's than it is today. Now we have 53 x 39 or 50 x 34 chain rings at the front and 11 speed blocks (I mean cassettes!) at the back. We now have any combination gearing we want from 11 teeth to 27. We don't need to know the details, but this has become achievable by lengthening the cage on the rear mech as materials and technology have advanced.

Anyway, we now have many, many more gear options from which to choose, so we should be able to keep in our optimal cadence range at all times. Which brings us to our first stumbling block. What's optimal? We'll come to that later, but first more theory!

Trigonometry ~ Back to School

Cadence is affected by many factors.

Over one of which you

have no control. Your leg length, or to be more precise your thigh

length. Longer levers exert more pressure for a given force but

are harder to move fast. Think wings of an Albatross versus the

wings of a Humming Bird.

You can optimise this genetic gift/hindrance (delete as appropriate) by getting the crank length that best suits your leg length. We now have "standard" options from 170mm, 172.5mm, and 175mm. Long legs, generally, need long cranks.

The longer the crank the bigger circle it has to turn, and distance it has to cover, to complete a full revolution.

A 170mm crank covers 1068mm for one revolution, a 175 crank covers 1099mm .

By necessity, covering a larger distance for a given revolution slows the rev rate of your pedalling. Not always a bad thing, but can be.

Everyone say's track cyclists have the highest cadences, and generally that's right. But track cyclists, so they don't clip the floor when on the banking, ride 165 mm cranks. As above, shorter cranks spin smaller circles so can be spun much quicker than 175's.

It's just science and that's how things work. Little levers, make complete circles, quicker than big ones.

So, for optimal cadence you need to find your optimal crank length. You won't always know when you've got it right but you'll immediately know when you've got it wrong. When I road test bikes, if they haven't got 172.5 cranks I can tell within the first ten pedal revs!

Most people settle for the cranks that came with their first bike and will ride that size for ever more. If that's what you've done, then don't fret. If you're used to it, leave it. Try something different in the winter by buying a cheap chainset off eBay, or borrowing a mates' and going for a pootle in low gears to get the gist of the difference.

Cadence + 20

When I initially try to get people to pedal faster their

first move is to go from say 90 rpm to 110 in one hit. They

fatigue very quickly, bounce all over the show, say it's rubbish and go back to their comfort zone.

I let them do this to prove my

point and to get them to see how bad it is. We make a big thing

out of it and we laugh at the absurdity of it all. Then we go

about changing it.

Which is where muscle memory comes in to it. We've known about this phenomenon around 2000 years when Galen (no, not that one) realised that the brain consciously controls the muscles.

However, if you do a

repetitive task often enough your brain "scales down" it's monitoring

activity and lets your body get on with it all of its own accord. Freeing up brain power!

However, if you do a

repetitive task often enough your brain "scales down" it's monitoring

activity and lets your body get on with it all of its own accord. Freeing up brain power!

Just to show I'm not making it up, I've successfully used these cognitive development techniques, in a previous life, when I developed Software for the Mind. It also works on cyclists.

An example? You don't have to think about how to walk, you just stand up and do it. Under normal circumstances, you don't have to think about how to pedal. You just do it and your brain lets the muscles crack on and settle in to their rhythm. Which is all nice and cosy but what if it's not a particularly efficient rhythm and has been holding you back all this time?

When you try to up your cadence for extended periods of time you really, really, really have to think and concentrate about the task at hand. Your breathing goes to pot, you get stressed and it's all too easy to snick it up a gear.

Changing your "natural" cadence is hard work but it pays off handsomely if you persevere. It's a lot more difficult, but a lot more rewarding, than you'd first think.

The Bounce Test

Bouncing in the saddle isn't a good look. During our early winter

training rides we have a 500 metre "race" where we all choose our lowest

gear and spin, in the saddle, to the imaginary finish line.

It's meant to be fun, and it is. It's one of the funniest things you'll see on a bike. The slowest sprint in the world, with leg speeds of 140 rpm plus, and with grown adults laughing like drains. But it serves a serious purpose. Everyone finds their "bounce point". Their next objective, throughout the rest of the winter, is to move this bounce point higher up their rev range.

Try it yourself on the road or turbo. Just make sure your food, gels and mobile phone are all secured in your back pockets before they fly up the road.

Ride in a gear lower than normal for the road conditions, and get to your natural cadence. Very slowly, start adding a rev at a time (say every 30 seconds) until you start to feel slightly uncomfortable. Now, concentrate on your breathing and leg patterns and try to keep everything in synch. When you start to bounce, monitor your sensations, thoughts and actions; then just back off a rev or two.

You bounce because your leg muscles and foot aren't relaxing in unison at the bottom of the stroke like they do when you pedal normally. The timing of your highly sensitive internal clock is out and it's not happy.

Because you're going faster than the norm, your leg muscles are misfiring when the foot hits the bottom of the stroke. As the foot obviously can't go past the end of the crank, the bum moves away from the saddle. Resulting in the dreaded bounce.

Addressing the Problem

First off, you need to check your saddle height. Too

low, you'll start bouncing very early. Too high and you'll rock in

the saddle causing other issues. Get someone who knows

to check it out if you're unsure. Then check

your cleats and foot position. You should be aiming for the ball

of the foot to be slightly ahead of the pedal axle.

Finally, you need to practice pedalling circles. Just because your foot is constrained in to a tangential arc by the crank doesn't mean you automatically produce power for the full 360 degrees. It's a lot harder to do than you would imagine.

You've

all seen the people that pull their bikes out of the sheds in the spring

and go for a ride while the weather's nice.

You've

all seen the people that pull their bikes out of the sheds in the spring

and go for a ride while the weather's nice.

Brilliant, I'm not knocking them, at least they're having a go. But we've all seen them too low in the saddle and stamping on the pedals.

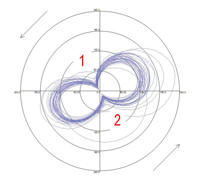

This is how their power production looks through a power analysis system.

1 & 2 are the dead-spots where no power is produced. You see they almost meet in the middle and form a figure of eight. Mildly effective, the bike moves forward, but not very efficient.

At some point or another we all pedal like the recreational cyclist above. We stamp on the pedals as we get tired or hit a stupidly steep slope. Don't beat yourself up about it, just do something to address it and make sure it's a one-off not the norm.

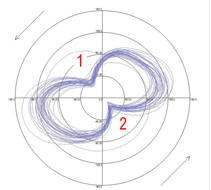

This

is a reasonable club cyclist. Less of a dead spot at the six

o'clock positions but you can see that dip 2 is closer to the centre

than dip 1.

This

is a reasonable club cyclist. Less of a dead spot at the six

o'clock positions but you can see that dip 2 is closer to the centre

than dip 1.

One leg is obviously stronger than the other!

The output is smoother than the above shot, you can see the

lines are closer together but not what you'd call round at the

extremities.

Reasonably effective and reasonably efficient, as you would expect from a good road man.

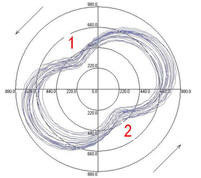

Okay, this is how a pro pedals and why they look like swans and we look like ugly duckling's.

We've moved from a figure of eight, to a peanut, to a sausage! Pedal force is all the way to the edge of the chart, the dips at 1 & 2 are still there but much less pronounced.

More force, for more of the circumference, gives a very effective and a very efficient pedal stroke. This is why we finish sportive courses an hour behind the pro's!

Concentrate on pedalling a full, fluid circle. Guide the foot around the circumference of the full pedal stroke. Don't just push down hard from the two o'clock to six o'clock position and let the momentum carry you past the dead spot.

As an aside, it's the dips at points 1 and 2 that the Rotor and Osymetric chainrings are trying to eliminate.

Anti-Bounce Training Drill

A very easy drill to address you pedalling inefficiencies

(don't worry we've all got them) is the one legged pedalling

session.

First off, try it on a turbo or a VERY quiet road, preferably slightly down hill, Get the bike in a light gear and unclip one foot, hold it clear of the flailing pedal and for fifteen seconds just try to pedal in a nice fluid circle. It's a lot harder than it sounds.

The first thing you notice is the awkwardness at the bottom of the stroke. That's the bit you concentrate on first. You are not trying to push a big gear or make your legs stronger; so use smallish gears and smooth out that dead spot. Then swap legs and try to build up to a minute at a time.

When the bike stops lurching forward like your swimming the breast stroke, you've got it cracked. People talk about "scraping mud off your boot" at the bottom of the stroke. To be honest, I don't go for that. Relax your foot at the bottom of the stroke, think circles and DON'T scrunch your toes and try to drag the pedal around. There should be no tense areas of your body. Relax your way to speed.

Fluid pedalling is efficient pedalling and efficiency leads to economy of effort and saving effort wins races. All you have to do is be smooth, relaxed and circular. How hard can it be? See above; or below!

Think Fast Think Smooth

When riding on the road, between intervals or on any

endurance or recovery ride, keep asking yourself the same question.

"Can I knock it down a gear and spin faster?" The answer is always

yes. Even if it's just for twenty to thirty seconds.

Keep trying this and keep thinking, always, can I change down. After a couple of weeks you'll be spinning like a good 'un and doing it without thinking. If you don't know what to do, change down. And never, ever, ever, waste an opportunity to pedal downhill. We'll come back to this in another factsheet later in the season.

How to Pedal

A lot of riders try to pull up on the pedal with the upcoming leg.

Mainly because it's one of those "traditional" training methods that

seems to have stuck over the years.

But to my mind that steals that leg's recovery phase. You don't have to pull up, unless you're on a really big climb, just take the pressure off the pedal. Don't have your upcoming leg working as a dead weight against the down pushing leg. This game is hard enough without adding lingering limbs to your challenge.

Many, many riders here in Jersey have tried Power Cranks (the ones with a ratchet system) but they only ever use them for one winter. I've never seen them being used two years running and the same pair has changed hands around ten times on the second hand market!

Bernard Hinault, Marc Gomez and Eddy Merckx (all personal acquaintances of Mrs Flamme Rouge) never used Power Cranks, or power meters come to that, but that's for another day.

They won their respective Monuments through fluid, efficient, effective pedal strokes and more than a smidge of raw talent.

There's many a talented cyclist that pedals anything but smooth.

Our friend Jens Voight is one but there's only one Jens and we don't have the other physical, psychological and physiological factors that he has. So we need to learn how to pedal.

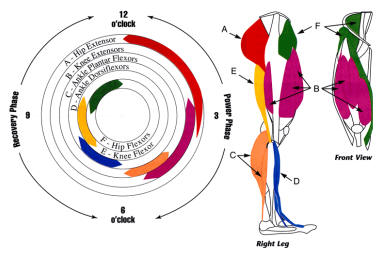

Here's a physiological chart of the muscles you use, and when you use them, to propel your bike onwards and upwards. It all starts from the bum. It's one of the biggest muscles in your body and for some of us it's getting bigger. Use it well, it's not just for sitting on.

Why this is important

How many pedal strokes do you use for your event?

Here's a few rough figures.

Local Crit; Quennevais 10 laps, avg cadence 103 rpm, time 29 minutes, 2987 pedal revs.When your doing a repetitive task this many times it doesn't take a genius (it didn't) to work out that small individual gains can give massive returns.25 mile Time Trial; time 60 minutes, average cadence 94 rpm, 5640 pedal revs.

Local Road Race; 6 laps Hougue Bie, avg cadence 89 rpm (lots of freewheeling), time 1:50, 9790 pedal revs.

Big Sportive; Bernard Hinault, avg cadence 91 rpm, time 5:41, 31031 pedal revs.

Super Sportive; Quebrantahuesos, avg cadence 87 rpm, time 7:17, 38019 pedal revs.

Cadence, not just the quantity but the quality, is vital to helping you realize your potential.

The Gains in Numbers

Let's start with a 10 mile and 25 mile time trial.

I

know there's some of you out there because my Time Trial plans account

for almost 50% of my output!

Let's start with a 10 mile and 25 mile time trial.

I

know there's some of you out there because my Time Trial plans account

for almost 50% of my output!

Even though the last time trial I did was in the Rider Man two stage sportive in 2004, I do know how to make people faster in them!

Before we start: The numbers in the chart refer to gear development (Johnny Foreigner method) which is the distance (in metres) travelled by one revolution of the crank in that gear.

So, lets start with a ten mile time trial. We'll assume we've just rode one at an average cadence of 96 rpm, in a 53 x 16 gear which gives 7.0 meters covered per crank revolution. That would give us 2300 pedal revs, a speed of 24.86 mph and a time of 24:09.

If we used the same gear over the same distance but would spin it at 97 rpm, we'd achieve a time of 23:54, knocking 15 seconds off our time. At 96 rpm you cover 768 meters per minute; at 97 rpm you cover 776 meters per minute.

Extrapolate that out to a 25 mile TT and you'd do an hour and 20 seconds at 96 rpm; a good ride but you'd probably feel a tadge miffed. At 97 rpm you'd knock 37.5 seconds off your time, be under the hour and on a high for the rest of the week. The margins really are that close.

Guenrsey 1990 Easter Festival 25 TT

If you're not a time-trialler, think how much fresher you'll be for the sprint if you can save all of your fast-twitch muscle action for the last hundred metres; rather than burning them all up in the previous hundred kilometres just to get you there?

The

Message

I'm not asking you to train harder, just

asking you to pedal smarter. This improvement in within all of

you. All you have to do is think about pedalling smoothly and keep

thinking about pedalling smoothly until you don't have to think about it

any more.

We're actually going to get 1% faster just by thinking about how we generate power throughout the whole pedal stroke. Once you do we can then think about adding a rev a month to our average cadence.

You might not manage it every month but come the end of the season you should be 5-6 rpm higher than you now are. If you carry this in to the winter and can add another two or three rpm over the out-of-season low gear endurance phase, you're well on the way to gaining significant power production for free.

Efficient pedalling is the icing on the cake you've made through training hard. Races are won by the smallest margins. If you can sprint one rev faster than the rider next to you, you'll win the sprint by around 8 metres. And when's the last time anyone did that?