Climbageddon Training...

Muro di Sormano ~ Fabio Casartelli Sportive

11 kms with 1.7k at an average 17%

This is why we climb slowly in the winter...

Every January, in the cold, wet, windy, depths of winter, we undertake our infamous flamme rouge Climbageddon Rides. Locally, they're amongst the hardest and, surprisingly, most popular of our training sorties.

Meanwhile, elsewhere around the world, there are thousands of riders tackling "Hilly Road Rides" over the challenging lumpy terrain laid out before them. But sadly, many riders fail to make the most of the alternative, valuable, training opportunities these contour lined lumps offer.

Here, I'll concentrate on the scaled down, "local scene", but I'm sure you can relate it, or extrapolate it, to your own particular, ride, group or circumstances.

How it should be...

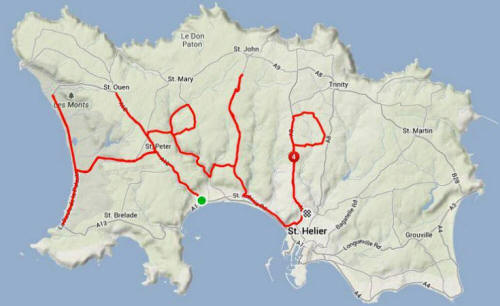

Our local Climbageddon's make best use of the limited terrain we have

in an island measuring just nine miles by five. With a maximum height of

around 100 metres, and our longest, sustained "climb length" of 1.5

kilometres,

we have to be creative on how we prepare for our

mountain assaults.

Climbageddon 10, is our first "green week" ride. As it's name suggests, we complete ten climbs. The following "amber week", has a gritty fifteen ascensions, and the concluding "red week" has a back-breaking twenty. Before we return to just ten, for our "grey" adaptation/recovery week!

Climbageddon 20 Profile

In four, consecutive weeks, we take on fifty-five tough, steep, labourious, leg-sapping, climbs. Admittedly, they're not alpine long, but they are the best, and only ones, we have. So we need to maximise our use and physiological return from the opportunities they offer. But what they lack in height and length, they make up for with quality.

The

prime objective of these sessions is to increase

muscular endurance, a vital component of

a cycling athlete's toolbox. Muscular endurance, as its name

suggests, is the ability to generate muscular power for an extended

period of time. The clue's in the title ~ muscular!

The

prime objective of these sessions is to increase

muscular endurance, a vital component of

a cycling athlete's toolbox. Muscular endurance, as its name

suggests, is the ability to generate muscular power for an extended

period of time. The clue's in the title ~ muscular!

Muscular endurance is what burns riders off the wheel, it's what drives a breakaway, it's what powers a chasing bunch.

Muscular endurance destroys the opposition; mentally as well as physically. Muscular endurance is the stuff that does the real damage out on the open road.

Ask the legendary bunch engines, Jens Voigt or Vasil Kiryenka. These riders are half man, half machine. And it's all down to their muscular endurance, their ability to suffer and, more importantly, their ability to make others suffer.

The whole premise of these rides is to push the muscle to the edge of its capabilities. We want our muscle to fatigue before we maximise our oxygen uptake. So it's important to minimise oxygen demands and (to quickly repay the inevitable oxygen debt) maximise recovery before we hit the next climb.

We do not want to carry any residual fatigue, lactate or oxygen depletion in to the next climb. That comes in the pre-season, Classics Circuits. For now it's push as hard as you can on the pedals, then ride as slowly as you can to the next climb. Maximise your opportunities to improve your muscular strength and power.

During these sessions we are not interested in cardio-vascular endurance. That will come from our mid-week turbo work and weekend rides a little further down the road. For now, it's all about the muscles; nothing else matters, especially your finishing position on the climb.

Okay. I think I've laboured the point enough now, but pay attention, there may be a test later.

Why it should be...

To maximise muscular endurance, you need to

take the muscle to the edge of it's comfort zone and beyond.

You need to work it harder than it wants to work but without taking

it to the point of failure.

Think of it as stretching an elastic band as far as you dare.

But if you go too far and snap it, you've lost!

There's only one way to do this...

You need to climb, in a gear that's slightly harder than you like, at a cadence that's slightly lower than you'd like, at a speed that's much slower than you'd like! We're not feeding ego's here, we're building race-winning, and speed-climbing, potential.

These sessions seem to contradict everything you expect about performance cycling. Grinding up a hill, as slow as you can? Making it as hard as you can? How can that make you a faster rider?

It's not a pleasant experience,

but neither is it painful. It

takes confidence, it takes concentration and it takes discipline.

It's not a pleasant experience,

but neither is it painful. It

takes confidence, it takes concentration and it takes discipline.

It is totally contradictory to everything your mind, ego and instinct is telling you. But to ultimately climb like a champion, do it you must.

Why try to be the slowest up a hill? Because, paradoxically, the payback is exponential to the input that's why!

A few weeks of this and you'll be ready to clear killer climbs like the mighty Redoute, in the Classics Monument, Liege Bastogne Liege sportive. 1.7k at 9.8%, with ramps at 25%.

Just like Dianne, (mrs flamme rouge) has above. Not the fastest rider up it, but she cleared it and cleared it ahead of many others, some of which had to get off and walk!

One of the big differences between winter and summer is that (generally) in the winter, you train to race. In the summer, you race.

We all know medals are awarded in the summer, but they are won in the winter. Winter is the time to suffer and suffer well.

For all our sessions, the mantra is the same. But especially for the Climbageddon's, it's vital to remember, "we are training, not racing".

flamme

rouge Road Captain

Chris Stephens

Doing some serious hill damage, in the Roger Walkowiak Sportive

Muscular endurance, on the tops ~ the others are on the hoods or out

of the saddle!

How it is...

As soon as any club run, chain gang, or group of mates

anywhere in the world,

get to the base of a hill, the climbers get to the front, line it

out and go as hard and as fast as they can. Dragging with them the

indecisive, unenlightened or less-disciplined souls of the peloton.

Because everyone loves to race.

The climbers obviously get to the top first. Further enhancing their reputation; and reinforcing to those behind that they, themselves, are rubbish climbers and need to practice faster climbing!

The physically (and mentally) strong riders, stick with the programme. They churn the gears, get dropped, then pick off the oxygen-debt ravaged "chasers" one by one.

Further reinforcing to the chasers dropped by the climbers, and caught by the strong, clever riders, that they are rubbish at hills and need to practice climbing faster!!

But what have our ascent winning climbers actually achieved?

They are already great climbers and have won the climb; but have they developed their musculature? Have they become a stronger rider for ascending victoriously?

Their leg speed, heart rate and cadence were higher, faster, bigger than everyone else's; but has this effort made them a faster or stronger rider?

Has their muscular endurance, lactate tolerance, core strength, or oxygen uptake improved by winning this, or any of the other day's climbs?

The answers to the first two questions are; no, and no. The answer to the third is no. An the answer to the final conundrum is, unsurprisingly, no, no, no and no!

In reality, all the excellent climbers have done is get to the top of the climb a minute quicker than everyone else; which means they have to wait around in the cold while the "non-climbers" (or more specifically those not racing it) catch up.

Extrapolating this out, over the course of

the Climbageddon's, the "climbers" can be hanging around for up

to fifty-five minutes waiting for the weaker, and stronger, riders

to arrive.

Extrapolating this out, over the course of

the Climbageddon's, the "climbers" can be hanging around for up

to fifty-five minutes waiting for the weaker, and stronger, riders

to arrive.

Or to put it another way, "the riders who stick with the programme" are banking an extra fifty-five minutes muscular endurance training! How fantastic is that?

Fifty-five minutes, guaranteed speed enhancing, muscular endurance building training work, from the very same rides.

Now I've got your attention!

Starter for Ten...

Climbers have a rare physiological gift that all of us wish we had; this mainly

revolves around a large lung capacity, huge oxygen uptake and the

lactate clearing and tolerance attributes this allows.

The problem with natural climbers, is that many fail to take advantage of this rare genetic gift, by developing it further, to use it to stoke the fires of other "race winning" training adaptations.

Almost all of us do what we're good at. We're good at it, we like it, it makes us feel good; it panders to our ego and neutralises our insecurities. So climbers climb; as fast as they can. Why wouldn't they?

Have you noticed, at the very top echelons of the sport how most of the good climbers are also great time trialists? It doesn't always necessarily work the other way around, but Froome, Wiggins, Martin, Evans, Indurain and many more climbers can mix it in the TT's.

Especially a Grand Tour TT. When a couple of weeks in to the race, just as everyone else is spent, a full-on 50 kilometre "muscular endurance" effort is often required.

Carsten Koppen ~ full gas (as always)

So use one gift, your aerobic climbing capacity, to prime another, your muscular endurance capacity. Muscular endurance is the answer to almost all your cycling questions. Build it, use it, win with it.

But before we go any further; we are talking muscle endurance. Not muscle size. There is no need whatsoever, unless you're a track sprinter, to get in the gym and start squatting or bench pressing weights. Muscular endurance has nothing to do with muscle size. So with that caveat, lets move on.

Oxygen Uptake Mistake

Racing a climb, obviously has to be done at some point. And we

do, come the next phase of our structured, periodized, training.

But not now.

Before we work the lungs we need to build the muscles. There's no use having 500 watt lungs if you only have 200 watt legs. We need to develop the bike powering muscles and their related infrastructure.

To maximise oxygen uptake we need to condition the surrounding connective tissues, enzymes, structures, and physiological adaptations within the muscles, to be in a position to allow us go faster when we need to. When we race.

Racing a hill too early in our preparation causes us to draw on huge amounts of oxygen (and glycogen). At this time of year, it's normally cold, damp air that we breath in. And that's not good!

Racing the hill, requires high leg speed, which demands a high oxygen supply. This requires a high breathing rate, creating a high heart rate, with causes high lactate build up, producing excess ionization imbalance within the muscles.

Everything is high. And here's why that's not a good thing if you want to improve as an all round rider. And ironically, especially if you want to improve your climbing.

We've covered this generally before, but here we'll deal with specifics. The numbers are arbitrary to prove the concept, they are in no way definitive, but the evidence stacks up, just go with it for now.

Your VO2 (oxygen) "consumption" is effectively the amount of (red) arterial blood oxygen, pumped from the lungs, minus the (blue) venous blood oxygen, returned to the heart.

Oxygen sent out, minus oxygen returned, must equal oxygen dropped off during the muscular contraction gas exchange.

And remember, oxygen equals power and speed. So you want to "return" as little as possible. Returned "clean" oxygen is effectively wasted (or non-realized) power. It also takes up the space that could be used to transport, and expel, debilitating CO2.

The "consumed" oxygen is dropped off in the metabolically active muscles. Which is why we remain seated when doing the Climbageddon's.

We don't want to get out of the saddle and "activate" the upper body muscle mass. This just diverts much needed "leg oxygen" to help support the shoulders, arms and chest. We want all our resources (at this training point) in the legs and the core driving the bike onwards and upwards.

Your heart rate rises when you stand to climb because it has to pump more blood, to more muscle mass, to keep supply with demand. So stay seated and keep your heart rate under control.

So our objective, as racing cyclists, is (and always will be) to get as much oxygen from the air outside our body, in to our bike-propelling muscles, and back out again. As quickly, efficiently and as effectively as possible, for the least metabolic cost we can manage.

The Maths

Screaming up a hill, even for gifted climbers, causes rapid and shallow

breathing. Obviously this has an impact on oxygen uptake.

Breathing in this fashion, you realize 80% of your lung capacity instead of the potential hundred percent that a slow, steady, deep, rhythmic breathing pattern would allow.

So, already, you are 20% down on your optimal oxygen transfer, and power producing, potential.

Some will say, but I'm breathing faster so it averages out. A good answer; consider a career in politics instead of cycling! The theory sounds good but our bodies don't work that way. To prove it, try pumping a tyre with a mini-pump using "half strokes". You'll soon get the picture.

Okay, we now have 80% oxygenated blood, heading for a heart that's pounding out of our chest at a rate, say 10%, higher than it could be.

The speed of the blood passing through the body, and

the lack of red blood cells, enzymes and mitochondria in the muscles

(due to a previous failures to ride slow and build a solid base), prevent a full

gas-exchange drop

off, and CO2 shuttle, back to the lungs to breath out.

The speed of the blood passing through the body, and

the lack of red blood cells, enzymes and mitochondria in the muscles

(due to a previous failures to ride slow and build a solid base), prevent a full

gas-exchange drop

off, and CO2 shuttle, back to the lungs to breath out.

The rapidly flowing blood can now "drop off" only 80%, of its 80% oxygen saturated payload.

Our cardio vascular system is now "out of synch" with our respiratory system. Also, the pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation systems are "out of harmony".

How many times have you heard (you hear it a lot on our rides) "sit down, calm down, and synch your breathing to your pedalling".

Keep everything calm, steady and in harmony. A calm rider is a fast rider.

Meanwhile, back at the climb! To recap; a high heart rate is forcing blood to rush through the lungs so fast it can't pick up a "full load" of oxygen. The fact that rapid breathing has made oxygen saturation lower than optimal, just makes a bad situation worse.

Yep, we're the fastest up the climb, and won the short-term competition, but have we made a long-term contribution to our ongoing fitness improvement. I'd suggest not.

Even if you've followed other parts of our programme and ridden slow enough to create a required base, which have allowed us to develop a higher volume of plasma, and a greater density of mitochondria and red blood cells, screaming up a climb has not allowed a realization of the benefit those sessions have accrued.

The Sums

Percentages of percentages are a strange thing to get your

head around, but we'll give it a go to prove our point.

Say a rider, climbing in a (I'd say slow, but racers don't like the word "slow") controlled fashion, breathing deeply, rhythmically, in a high gear with a low cadence, is given as our 100% baseline. What does our theoretical speed climber achieve in comparison?

Our rapidly breathing, leg spinning, summit winning climber is running at 80% oxygen pickup, and 80% drop off. Which means they are realizing 64% of the metabolic efficiency (80% of 80%) of their controlled, climbing compatriots.

They are also doing this with a heart rate 10% higher than the ideal! So minus another 6.4% (10% of 64%) from that efficiency, and we now drop in to the region of 48% comparative efficiency.

And that's before we take in to account that they only spent four minutes racing the climb whereas the "controlled" riders took five minutes.

So our climbing climbers are now looking at a relative 48% "training adaptation" for 80% of the time, when compared to baseline riders.

Our baseline "strength building" riders, breathing deeply and rhythmically, have maximised oxygen pickup. Due to slower heart rate and blood throughput, they also maximised oxygen drop off (and more importantly CO2 pickup), for a 100% of the available time.

And that's on just one climb out of the fifty-five!

All my "climb slow" mantra, should now begin to make some sort of sense. Follow this protocol and you will climb infinitely quicker when it matters; in the races. You train to set Strava KOM's, you don't set them in training.

flamme

rouge

attacking the summit at the top of the world

2284 metre Colle di Sameyre 18k @ 7.7%

Fausto Coppi Sportive ~ Cuneo

How it could be...

Those of a stronger (or competitive) disposition could always start

last and have their "wait" at the bottom of the climb. Leave

it as long as they dare, then climb with the aim of getting to the

top at the same time as, or within ten seconds of, the "normal"

riders.

Or, when they get to the summit, turn around, go back down to pick up the last rider and bring them up to the top, as over-geared as they need to be to stay with the rider and finish behind them.

So, as you can see, there are many ways the "climbing specialists" can endear themselves to us normal, genetically challenged specimens.

Which would make a change from us swearing at them as they put us in the pain locker and show us how much we have to improve. Just wait till the sprint, we keep telling ourselves!

The Message

Personally, and I totally understand why, it's hard to explain to

riders, that are smashing you on the climbs, to ride slower!

It's not for my vanity, so I can keep up. I'm too old for all

that nonsense now; I know my limits!

But again, as with all things cycling related, it's all counterintuitive. It needs a leap of faith for three weeks to fully understand the benefits you can reap in the spring. But once you've done it, you never look back.

No one is going to win a Strava KOM in the depths of winter, with three layers of clothing, a training bike and a screaming winter head wind. So why batter yourself trying. Why not put your training rides to good use? Train yourself to be faster.

You can make preparations now, to put a KOM out of all

reach come the late spring or early summer. Plant the seeds

now so you can reap the harvest later and get in the races to line

it out on the climbs.

You can make preparations now, to put a KOM out of all

reach come the late spring or early summer. Plant the seeds

now so you can reap the harvest later and get in the races to line

it out on the climbs.

If you are a climber,

can you imagine how much faster you could climb if you had an extra

fifty-five minutes muscular endurance in your legs at the end of

this month? You could go from good, to great, or from great to

untouchable! All for going slower; how bizarre!

Your secret to riding faster for longer, requires your muscles to produce more power for less cost. This comes from a combination of increasing efficiency and effectiveness.

To be effective you need strong, resilient, muscles capable of banging out a consistently high wattage for longer than those around you.

To be efficient you need to get more oxygen in to your lungs and ultimately fully perfuse your blood. You need to make better use of what you have when it gets to the muscles by getting a rapid and complete oxygen/CO2 exchange. Then you need to get the CO2 fully expelled and keep lactate under control while at all times remaining calm.

Play the long game. Go hard, go slow, go steady. If you're always the first to the top of the climbs, you may be missing a trick. Come the spring, and the races, you'll be wondering why you're no longer leading the pack. How come all those slow, winter riders are now ahead of you?

It's normally at this point that climbers go out to ride the climbs even faster to try and "catch up". It rarely ends well.

But, don't worry, you'll have a chance to put it right next winter.

Until then. Good luck!